It’s boggling to calculate the ways this major pandemic has altered our perspective on things. Art, for example, means something different than what it did three weeks ago. It certainly functions differently, because so many other things have fundamentally changed—the public sphere is now an exclusively virtual space, the economy is morphing into something unrecognizable—time, space, work, leisure, life itself all shifting in their definitions. And just as art and culture are becoming more valuable tools for folks to navigate through a day, many working artists are without an infrastructure to support them; it is in a radical state of disruption. The scale has changed too—art has become more intimate, smaller, more aligned with everyday acts of living—things like cooking, dressing, working at a dining room table.

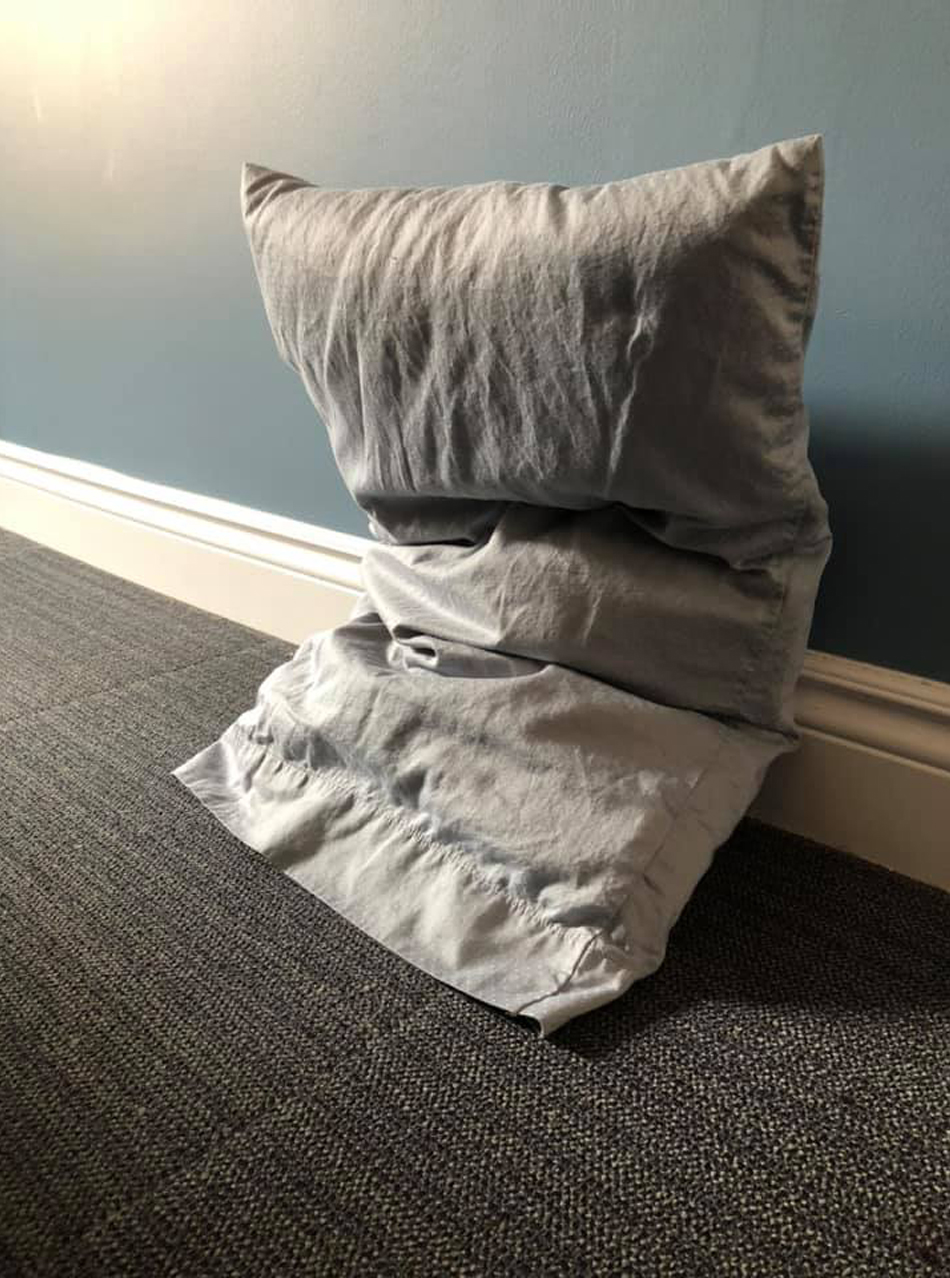

Almost immediately after the city started shutting down, artist Donna Akrey launched Studiolololol, a private Facebook group (as private as a growing membership of nearly 300 and counting can be) focused on simple daily art prompts. These prompts are elegantly simple, the sort of minimalist activities you might imagine doing on a sleep over with Yoko Ono. Prop a pillow against a wall in an intriguing way, photograph the top of your head, curate objects to sit on your hand—these are just a few of over twenty challenges that have now been issued. Two consequences follow from Akrey’s prompts: a friendly competition has been stoked within a community of very-creative minds (including many creatives from this city), eager to interpret the prompt as dynamically as possible. The second result is harder for me to describe, a kind of very gentle humiliation “why have I never been curious about the things that are around me?”—transformed quickly into weird elation—”I never knew I could be so inventive!”

“Studiolo” is an Italian word essentially meaning tiny studio, and has traditionally denoted a small, opulently detailed space used for creative work, scientific inquiry, collecting, or possibly all three. It is private space, but is also a proud space to show a shortlist of invited guests. Akrey’s impulse to identify social media space with an updated form of this word is cunning. It also is very consistent with Akrey’s own art practice, one that often takes to the mapping of spaces, to confronting and re-interpretating artistic traditions with comical verve, curiosity, and a love of everyday materials.

Another initiative that appeared on my Instagram feed seemingly the minute the pandemic arrived here was Adad Hannah’s Social Distancing Portraits. This is a series of videos posted to Instagram and other social media platforms that argues tableaux vivant as a very contemporary antidote to the kinetic aesthetics of our digital world. In essence, Hannah, in order to valve a sense of panic, walked out into his Vancouver community and began shooting video of citizens with a 70-200 zoom lens that would allow him to remain five meters or further from his subject (he is very stringent that he pursues this series of work according to current health standards). He would ask them to hold a pose for a photo, and then videotape up to 30 seconds of the subject in a state of near stillness, a brush of the wind or a quiver of the hand or eye the only clues that these are videos not photos. Furthermore, these videos are shown unedited, the speed is not adjusted, adorned only with original music by composer Brigitte Dajczer.

Adad Hannah, Social Distancing Portrait 2 – Jessica and Friend, 2020, video, music by Brigitte Dajczer

They end up being quietly disruptive on Instagram, a platform where still image and short video cohabitate, but are rarely mistaken for one another. When the eye adjusts to Hannah’s subtly changing portraits, the impact is immediate. These are people in a state of pensive inaction, and given the current state of the world it is impossible not to share affinity with them, feel the immediacy of that state of being.

“There is a friction between stillness and motion in these works, I think we all feel that very acutely these days,” he explained during a brief phone call, “we are trying to move but we can’t, we also can’t just stay still. In this way I think these videos really do speak to the moment.”

Another thing that has stuck with me from Instagram has been the sequence of tarot card designs showcased by Hamilton collage artist Stylo Starr. I had the privilege of working with Starr a few years ago here at the Gallery to present a series of works called 89 Dames, wherein she presented a history of stardom that focused exclusively on Black women. Her re-working of a Tarot Card deck is propelled by a similar urge: to recast the central archetypes of the Tarot—Death, The Fool, the Magician, Justice, etc.—as a complex expression of Black female identity.

Although Tarot Cards have been in use since the 15th century, their popularity as tools for divination peaked in Europe during a surge of popular interest in occultism in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The most popular incarnation of the deck was compiled by academic A. E. White and illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith in 1909, which, to some extent, standardized the structure of the deck. Starr uses Smith-Waite Tarot (also known as the Rider-Waite) as a template, and has designed 14 so far, working chronologically through the 22 cards that comprise the major arcana, before tackling the 56 cards of the minor arcana. Each work is assembled as a 12” x 7.5” collage so that they can best reflect a density and complexity of detail. The intention is to produce a fully functionable printed deck.

“I am letting go of a lot of things with this project,” Starr told me, “I just finished the Death card, which essentially is all about letting go, moving through big disruptive changes…and globally this is happening all over. This work seems to be personal and global at the same time.”

Starr’s project strikes me as a perfect creative response to the moment. The scale of playing cards seems to fit well within our current circumstances. The notion of our personal spheres suddenly blurring with more-global, more-cosmic spheres seems about right too. The urge to invest in rituals that will help us take stock, confront unknown aspects of ourselves, or divine some intelligence to prepare for the future is here like never before too. The evidence of Starr and Akrey and Hannah taking matters into their own hands, and meticulously fashioning for themselves a means to engage this uncertain future, is worth noting. It feels, in its own small way, heroic.

Header image: Stylo Starr, Death, 2020 collage.