Painters and sculptors have competed with one another since the days of Ancient Greece and Rome. The competition began as a debate about which of the two media better represents the world. For over 2,000 years, painting and sculpture have been inextricably linked, neither innovating without affecting the other. The Ancient Greeks and Romans painted and bejewelled their monumental bronze and marble sculptures to animate the figures in order to compete with the colourful frescoes and mosaics of ancient painters. The competition has roared furiously since the Renaissance as artists continuously seek means of outshining one another.

Art galleries are wonderful venues for observing how the two media activate and animate the spaces in which they are positioned. The Art Gallery of Hamilton, like many galleries and museums, has spaces devoted to both painting and sculpture, such as the David Braley and Nancy Gordon Sculpture Atrium. While grand picture galleries, atriums and courtyards highlight collections, the exhibition spaces where both painting and sculpture interact are frequently the most stimulating environments.

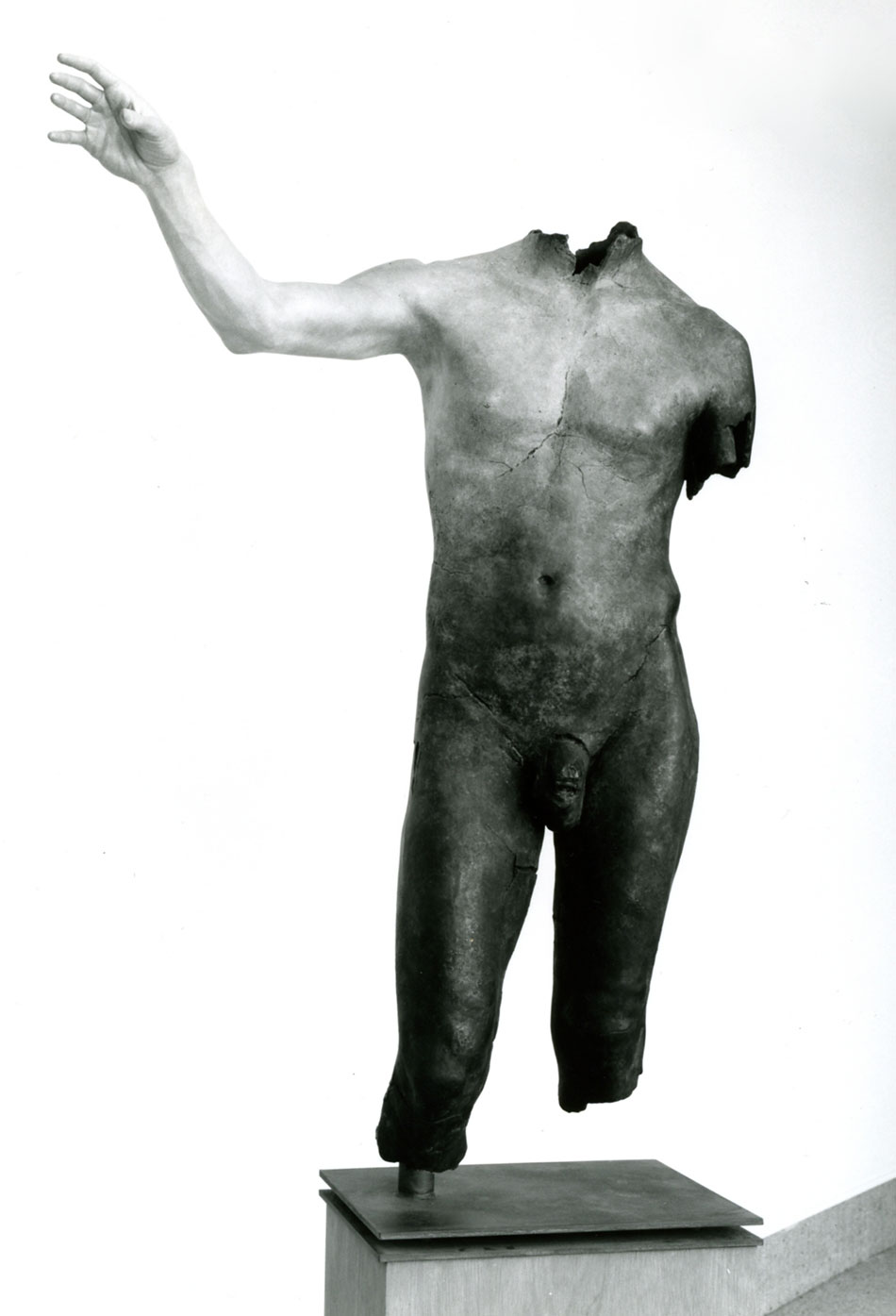

Art for a Century: 100 for the 100th is on view on Gallery Level 2, and within this exhibition you will find the Galbraith Memorial Gallery. Here we showcase works from our permanent collection, including Evan Penny’s bronze Shadow Torso (fig. 3), Prudence Heward’s painting, Girl Under a Tree (fig. 2), Jean-Antoine Houdon’s life-size plaster sculpture, the Flayed Man (fig. 4), and Jules-Élie Delaunay’s painting, Ixion Plunged into Hades (fig. 5).

The artists’ works—two paintings and two sculptures—focus on nude figures either posing, relaxing, or writhing. Heward’s reclining female figure (fig. 2) has all the physicality one would expect of sculpture in the round, whereas Penny’s half-length and headless torso (fig. 3) transitions from the lifelessness of dark bronze to the colourful detail of Heward’s painting. The detail devoted to the figure’s outstretched arm and delicately sculpted fingers is more characteristic of paintings, as demonstrated by Delaunay’s depiction of the rippling and muscular Ixion (fig. 5). By using colour in his sculpture, Penny ever so slightly breathes life into the seemingly lifeless bronze. Painters similarly enliven their figures by enhancing their realistic appearance. In each case, artists manipulate their media in an attempt to give life to their work.

Houdon’s Flayed Man (fig. 4) bridges the divide between the two arts. While his plaster was originally created as study for a larger sculpture, its widespread popularity as the most detailed life-size anatomical study made it ideal for artistic education—especially for the students at the French Academy in Rome where it was used. Students of both painting and sculpture began their artistic training by drawing from such anatomical sculptures before they specialized in one art form or the other.

By exhibiting paintings and sculpture in the same space, audiences are introduced to the inevitable visual interaction that occurs between the two media. Be it through light, colour, movement, or scale, each work enlivens the Galbraith Gallery not only by its own attributes but through the melange it creates as pictorial and material forms join to activate the space and engage the audience. Multi-faceted exhibition spaces, like the Galbraith, more often than not serve as nodal point—a space where both people and art intersect.