Early Snow: Michael Snow 1947–1962 opened one week ago, and we are so excited to continue exploring the dozens of works spanning Snow’s early formative years from now until May 24! The exhibition features an ambitious range of media including painting, sculpture, film, video, and works on paper—all from the first fifteen years of his career.

Today’s Exhibition Showcase explores the lone film work in the exhibition, A to Z (1956). This 16 mm short is Snow’s first surviving film, produced during his stint working after hours in the Toronto-based animation studio of future Yellow Submarine (1968) director George Dunning (1920–1979). At the time of A to Z’s production, Dunning was already an award-winning animator with his 1950 short, Family Tree, which tells the story of Canada’s settlement through animated paintings, sketches, and cut-out shapes. Snow’s film shows the artist similarly experimenting with animation using shapes and blue-ink drawings of everyday objects.

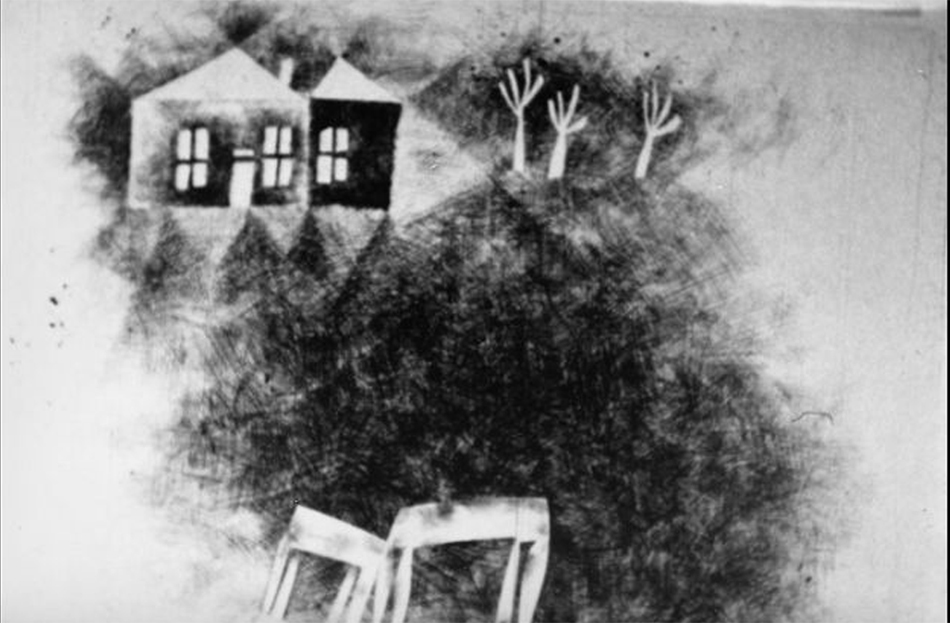

Within the film, objects dance around the screen; they are drawn in a crosshatched style, which, according to Snow, “came from a style of drawing that I developed when I was in Europe using blue ink, pen drawings.” [1] Snow’s work is less narratively-driven than Dunning’s, and its rough aesthetic emphasizes its experimental approach in contrast to the crisp, clear paintings of Family Tree. Reflecting on his initial interest in experimenting with the medium, Snow states, “When I made my first film, I didn’t know there was such a thing as experimental film, though I’d seen some of Norman McLaren’s work because George had shown us examples of what could be done in animation.” [2] An Academy Award-winning Canadian filmmaker, McLaren (1914–1987) innovated early experimental filmmaking in directions that clearly inspired Snow’s filmmaking. One of McLaren’s masterworks, the 1949 short Begone Dull Care, operates similarly to Family Tree and A to Z, with shapes and objects dancing around the screen accompanied by jazz music.

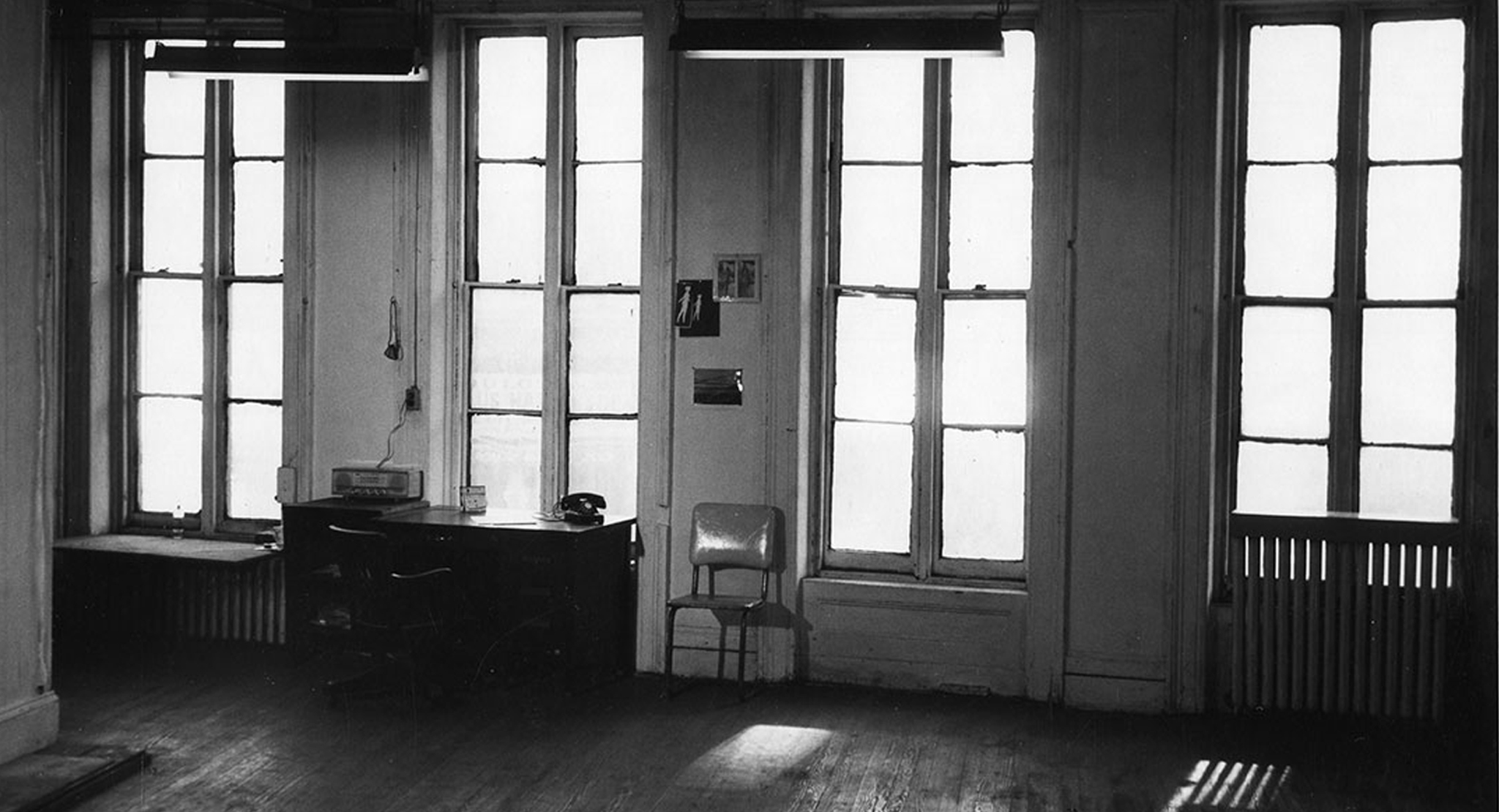

In 1967, a decade after A to Z and five years after the timeframe explored in Early Snow, the artist released his revered masterwork, Wavelength. Considered one of the most important films of all time, Wavelength is ranked #85 on the Village Voice’s 2001 list of the “100 Best Films of the 20th Century.” The work picks up many of the thematic concerns and motifs of A to Z, focusing heavily on physical space and the inanimate objects within them. Notably, both films contain the motif of the chair (also found in other works within the exhibition, such as the 1955 sculptural work Metamorphosis-Chair). Affirming the significance of this connection, Snow notes that the two anthropomorphic chairs in A to Z “prophesy the heroic presence of the yellow chair in Wavelength.” [3] Like the exhibition itself, the development from A to Z to Wavelength reveals how Snow’s formative works informed and inspired his masterpieces.

Be sure to head to the Art Gallery of Hamilton before May 24 to see A to Z and the rest of Early Snow for yourself. On February 27, don’t miss our 16 mm film presentation of Wavelength with Snow and Early Snow curator James King in attendance.

[1] Mike Hoolboom, “Michael Snow: Machines of Cinema (an interview),” Mike Hoolboom, 1993, accessed February 13, 2020, http://mikehoolboom.com/?p=112

[2] Mike Hoolboom, “Michael Snow: Machines of Cinema (an interview),” Mike Hoolboom, 1993, accessed February 13, 2020, http://mikehoolboom.com/?p=112

[3] Michael Snow, “Michael Snow: A Filmography by Max Knowles,” The Collected Writings of Michael Snow (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1994).