Here at the AGH, we are very proud of the collection of artworks we are fortunate enough to hold in our care. A curated selection of the over 10,000 pieces in our collection are on display on Gallery Level 2, accessible and free to everyone! One of the most asked-for works is an iconic sculpture: the Bruegel-Bosch Bus (1997–ongoing). Made by Kim Adams (Canadian b. 1951) as an ongoing work-in-progress, it has been on view for over a decade now.

Today’s Collection Showcase explores this massive installation on permanent display, situating it within Adams’s decades-long art practice. To learn more about the work, head to AGH Talks: Kim Adams and the Bruegel-Bosch Bus on Thursday, February 20th. Adams will lead a tour at 6:00 pm with a talk to follow.

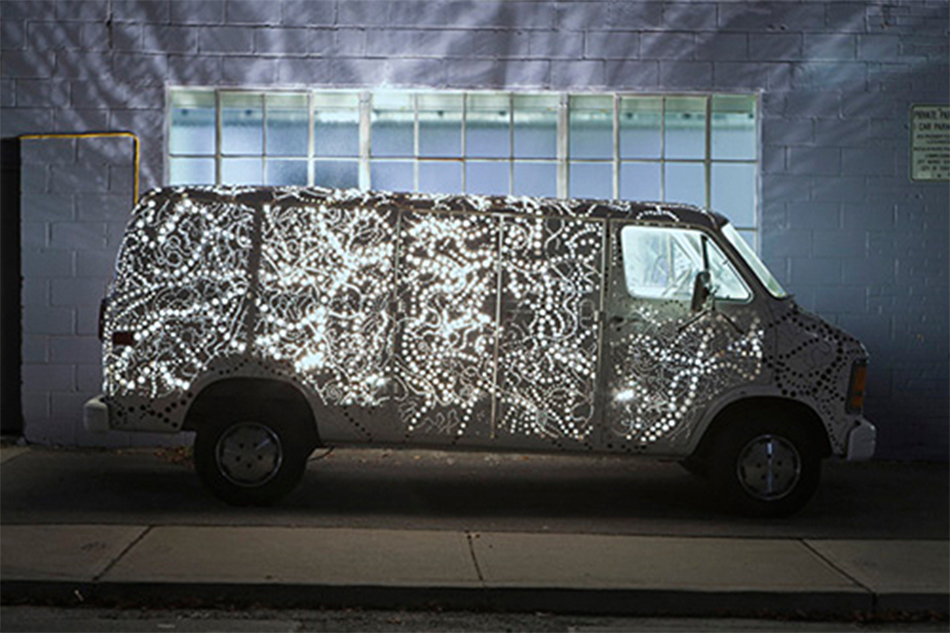

Approaching the world around him with equal parts troubled fascination and absurdist humour, Adams has been repurposing the physical components of everyday life into remarkable, often-enormous structures since the late 1970s. Throughout his career, Adams has created a variety of hybrid sculptures and assemblages composed of anything and everything, from hobby kits and toys to auto parts and entire vehicles. Adams’s 2008 work Autolamp, for example, repurposes the body of a 1985 Dodge Ram into a perforated metal lamp, glowing and emitting an array of light patterns from the truck’s interior. His 2010 work Love Birds re-shapes two Ford Econoline vans into an unusable, wheeled duo. These works strip vehicular forms of their function, shifting them into the purely-aesthetic realm. University of Waterloo Art Gallery Director and Curator Ivan Jurakic dubbed Adams “an engineer of the absurd, a master builder of dysfunctional objects.”[1]

While this title certainly fits, Adams often takes his projects a step further, creating functional objects—be they lamps, vehicles, or dioramas—at dysfunctional scales.

With Bruegel-Bosch Bus, Adams amplifies both the scale and dysfunction of his work, positioning an entire Volkswagen bus at the centre of the piece, then building worlds around it using toys, hobby kits, paper maché, train sets, and much more The large vehicle dominates the gallery space, with its overflowing contents reaching both to the floor and high above into the air. The scale of the work’s creation increases over time as well, as Adams regularly returns to the piece to add more objects to it. By continuously building this enormous work with such micro-scale objects of everyday life as action figures and toy cars, Kim works in two scales at once—a method Artforum’s Dan Adler describes as giving the viewer “a God’s-eye view of it being presented with a model-size analogue.”[2] In short, Adams creates a functional diorama at a dysfunctional scale.

Adams grants the viewer an omniscient perspective of the world circling the bus—a world not only nonsensical, but nearly apocalyptical. Amidst the chaos, a chain of Incredible Hulks comprise one giant Hulk mass, Shaquille O’Neal slam dunks on a large building, and tiny humans litter the landscape everywhere. Murray Whyte, formerly of the Toronto Star, interpreted the work as Adams as “gathering up in his arms as much of our taken-for-granted, cast-off consumer junk as he can carry and giving it a big, crushing hug.”[3]

Bruegel-Bosch Bus not only plays with a range of scales, consumer goods, and building materials, but also directly references the work of multiple artists. The work’s title names two of Adams’s artistic influences: the Dutch Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–1569) and Early Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450–1516). Bruegel’s Tower of Babel (c. 1563), one of the artist’s most famous paintings, depicts a similarly chaotic world centred around a large, complex structure. Bosch’s massive The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) presents Eden, Earth, and hell all in one work, complete with a range of interactions between humans and supernatural figures. Bruegel-Bosch Bus clearly demonstrates the influence of these two paintings, as Adams invites the viewer to get lost within the Bruegel-inspired dysfunctional structure and the Bosch-inspired dysfunctional society—driving both to the present in his toy-covered vehicle. “He grounds his work wholly in the here and now,” writes Jurakic, “to remind us that for all its quirks, ugliness, and folly, this is the real world we live in.”[4]

Want to hear more about this work from Adams himself? Don’t miss the artist’s free talk on Thursday, February 20!

[1] Ivan Jurakic, Under Deconstruction (Montreal: ABC Art Books Canada, 2006).

[2] Dan Adler, “Diaz Contemporary,” Artforum, accessed February 19, 2020.

[3] Murray Whyte, “Whyte: Bland objects made beautiful,” The Star, accessed February 19, 2020.

[4] Ivan Jurakic, Under Deconstruction (Montreal: ABC Art Books Canada, 2006).