Here at the AGH, we are very proud of the collection of artworks we are fortunate enough to hold in our care. From the over 10,000 pieces in our collection, we have selected a sampling to display in our exhibition, The Collection on Gallery Level 2, accessible and free to everyone!

In addition to The Collection, we are soon opening a new Special Exhibition, The Collection Continues: A Quarter Century of Collecting at our 2019 Summer Opening on June 20, 2019.

Exploring a piece from this upcoming exhibition, today’s Collection Showcase looks at Alex Colville’s 1992 painting, Traveller, a haunting work of understated storytelling.

Read up on David Alexander Colville’s life and career, and you will inevitably confront two images – Colville the artist and Colville the soldier. The man who would one day reach the highest level of the Order of Canada[1] brought his fine-arts background with him to World War II, returning having undergone, what he called, the “profoundly affecting experience” of painting the atrocities of war and concentration camps.[2]

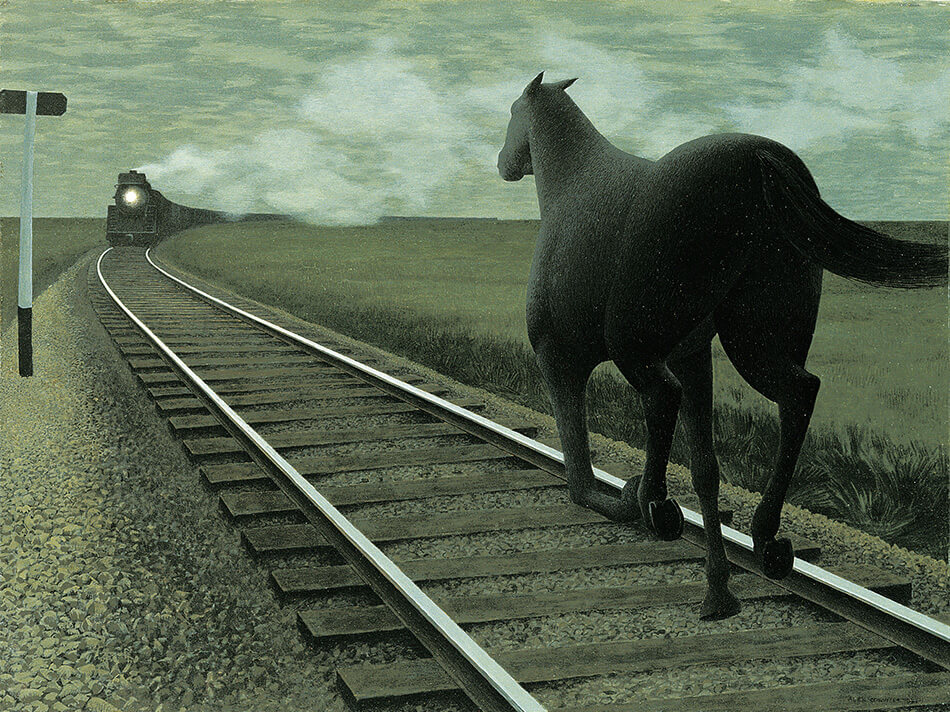

The bulk of Colville’s half-century artistic career did not directly address these military beginnings, as the artist returned home and shifted his focus from the incomprehensible chaos of war to familiar scenes of everyday life. He regularly painted domestic scenes, often even including tender moments shared with his wife and main subject, Rhoda. In other works, he depicted such everyday subjects as cars, dogs, roads, and houses, all in stunning detail. These scenes often lack comfort, however, as Colville contradicts his familiar subjects with compelling, haunting narrative composition. In one painting, a man stands at an open window against a rolling tide, a gun on the table behind him; in another, a horse and a train both display their speed and power, though directly at each other; in Traveller, a driver heads towards a dark figure against an icy landscape.

Colville implicates the viewer within the action of the painting, planting the perspective behind the wheel of the car, hands stretch outwards, steering the car. The figure outside could be anyone – a friendly stranger guiding us along the treacherous path, a menace leading us to our destruction, or even Rhoda, once again playing an active role within the painter’s life and artistic output. Moments such as these highlight Colville’s interest in “fascinating contradictions,” according to former AGO CEO Matthew Teitelbaum, noting that “his paintings are both difficult and accessible, both private and deeply resonant, both real in depiction and imaginary in association.”[3]

Colville thus plays in the middle ground between the familiar and the surreal, presenting everyday subjects in such a way as to force questions about those subjects’ placement within the painted world.

Colville, 72 at the time, even appears to have inserted himself within Traveller in the rearview mirror, visualized as just a forehead with sparse grey hair, marking his age and the painting’s placement within his canon. The work also reminds viewers of the iconic 1954 Colville painting, Horse & Train, as yet another manned vehicle heads towards a living being. Painted nearly-four decades later, viewers nevertheless experience the same narrative potential of an interaction – or perhaps, collision – between these two figures. We are now hyper-aware of the clash between living beings and machines – the possibilities of collision between horse and train, car and human, or human and the machines of war. Discussing these two works in tandem, Hamilton art historian and educator Regina Haggo noted that “Colville likes to focus on people leaving and arriving.”[4]

With these two paintings – one near the beginning of his career, the other near the end – we not only see the beginnings of two fascinating narratives, but the arrival and departure of the man who dedicated his life to portraying such powerful stories.

[1]John Northcott, “Canadian painter Alex Colville dies,” CBC, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/canadian-painter-alex-colville-dies-1.1309191 (accessed June 11, 2019)

[2]Andrew Hunter, “Welcome to Colville,” Colville. Ed. Andrew Hunter. Frederiction: Goose Lane Editions, 2015.

[3]Matthew Teitelbaum, “Foreword,” Colville. Ed. Andrew Hunter. Frederiction: Goose Lane Editions, 2015.

[4]Regina Haggo, “Haggo: Finding the extraordinary in the ordinary,” The Hamilton Spectator, https://www.thespec.com/whatson-story/6206620-haggo-finding-the-extraordinary-in-the-ordinary/ (accessed June 11, 2019)